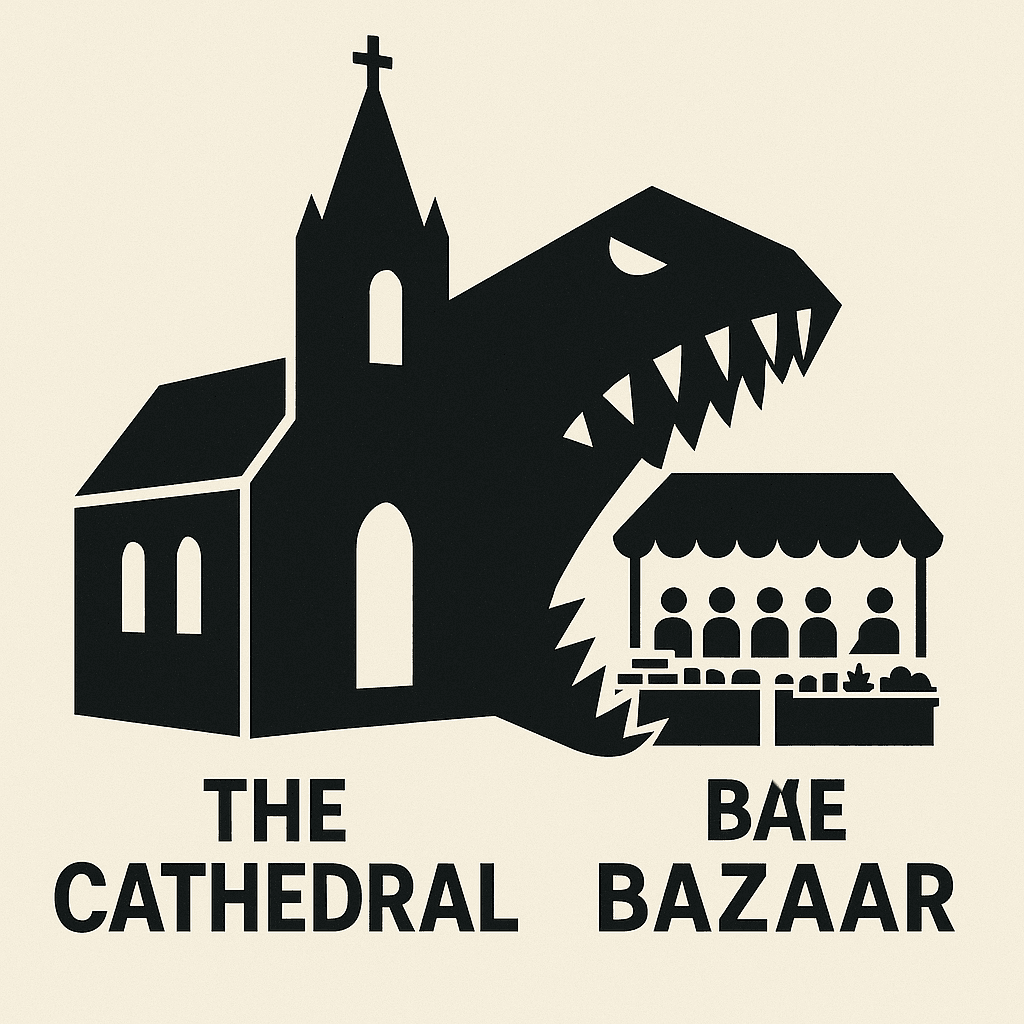

Introduction: Revisiting Raymond’s Metaphor

In 1997, Eric S. Raymond published his seminal essay The Cathedral and the Bazaar. He argued that software development could thrive in two primary modes:

- The cathedral — a closed, hierarchical model of slow, carefully managed releases.

- The bazaar — an open, decentralized model where anyone could contribute, innovate, and iterate rapidly in public.

Raymond’s thesis was revolutionary: given enough eyeballs, “all bugs are shallow.” He predicted that the bazaar would out-innovate the cathedral, and for a time, he was right. Linux, Apache, MySQL, and countless other projects proved that community-driven collaboration could rival—and often outperform—corporate engineering giants.

But fast forward nearly three decades, and the story looks very different. Today, the cathedral has not only survived but adapted—and, in many ways, it has consumed the bazaar. Open source still exists, but its freedom and accessibility are increasingly constrained by acquisitions, restrictive licensing, and centralized platforms. The bazaar is still noisy, but much of it operates under cathedral leases.

This essay explores how capitalism and corporate interests have overtaken open source, why it matters, and what must be done to reclaim accessibility and independence.

The Cathedral’s Strategy: Absorb, Restrict, Monetize

The story of how the cathedral consumed the bazaar follows a familiar playbook:

- Acquire influential projects.

Buy the commons, absorb its community, and integrate it into enterprise sales pipelines. - Change licenses or restrict access.

Rework terms so “free” means “free only if you don’t compete with us.” - Centralize platforms.

Make the infrastructure for open source development itself dependent on a single corporation. - Capture the narrative.

Rebrand community projects as “enterprise solutions,” aligning their identity with corporate goals.

The result is a paradox: open source is everywhere, yet the ability to freely remix, fork, and redistribute is harder than ever.

Case Studies: From Bazaar to Cathedral

IBM and Red Hat: The $34 Billion Turning Point

In 2019, IBM acquired Red Hat for $34 billion, the largest software acquisition in history. Red Hat had long been a poster child for proving you could build a billion-dollar business on open source, with Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) and a strong services model.

But the acquisition triggered cascading effects:

- CentOS EOL (2020): CentOS, a free downstream rebuild of RHEL widely used by startups, educators, and small businesses, was abruptly discontinued. In its place, CentOS Stream emerged—an upstream of RHEL that no longer offered binary parity.

- Restricted RHEL source (2023): Red Hat stopped publishing RHEL source freely, requiring customer subscriptions or CentOS Stream access. This made it harder for downstream distributions like Rocky Linux and AlmaLinux to promise identical compatibility.

What was once a hallmark of the bazaar—free redistribution and rebuilds—was narrowed to preserve Red Hat’s enterprise moat. The bazaar didn’t disappear, but it was fenced inside the cathedral.

Microsoft and GitHub: The Platform Cathedral

When Microsoft acquired GitHub in 2018, many feared a repeat of its “embrace, extend, extinguish” playbook. Instead, Microsoft took a subtler approach: GitHub remained open for individuals, but its gravitational pull deepened.

- GitHub became the default identity and workflow hub for open source. Issues, pull requests, and actions are so integrated that leaving GitHub feels like leaving the open source community itself.

- Microsoft tied GitHub into its cloud ecosystem (Azure DevOps, Codespaces, and AI-driven tools like Copilot), creating dependencies that subtly lock developers into cathedral structures.

Open source code is still on GitHub—but who owns the discovery, infrastructure, and workflows? Increasingly, the cathedral.

Elastic and Amazon: License Wars

Elastic built Elasticsearch and Kibana under the Apache 2.0 license. Cloud providers, particularly Amazon, offered hosted Elasticsearch as a service, often without contributing back proportionally. In 2021, Elastic relicensed its projects under the Server Side Public License (SSPL) and its own Elastic License 2.0.

This sparked the creation of OpenSearch, Amazon’s fork under Apache 2.0.

- The bazaar fractured into two competing markets.

- Developers faced confusion: should they use Elastic’s official builds with restrictions or OpenSearch’s community fork?

- Enterprises hesitated, adding legal reviews where none were needed before.

The result? Less accessibility, more friction.

HashiCorp and Terraform: From MPL to BSL

HashiCorp’s tools like Terraform, Vault, and Consul became staples of cloud-native infrastructure. For years they thrived under the Mozilla Public License (MPL).

But in 2023, HashiCorp switched to the Business Source License (BSL). This allowed free use for individuals and small-scale projects, but imposed restrictions on competitors offering managed services.

The community response was swift: OpenTofu, a fork of Terraform under the Linux Foundation, was born.

- Like OpenSearch, OpenTofu preserves openness, but at the cost of fragmentation.

- Terraform now has two ecosystems: one cathedral-aligned, one bazaar-aligned.

Again, the cathedral’s strategy was to restrict competition under the banner of sustainability.

Redis and the Valkey Fork

Redis, the ubiquitous in-memory data store, long thrived under BSD-style licensing. In 2024, Redis Labs relicensed its core under a commercial model.

The response: the Linux Foundation launched Valkey, a fully open fork of Redis. Many distributions and clouds migrated quickly.

The pattern repeats: openness restricted, fork required, bazaar fragmented.

NGINX and the Open Core Trap

NGINX began as a lightweight, high-performance web server beloved by sysadmins. In 2019, F5 Networks acquired it, shifting focus to enterprise bundles and advanced paid modules.

NGINX remains open, but the energy of the project increasingly feeds the cathedral’s commercial pipeline. Features once core to the bazaar now arrive gated by enterprise SKUs.

The Cost of Forks: A Fragmented Bazaar

Forks keep the bazaar alive—but at a cost.

- MariaDB vs MySQL: When Oracle acquired Sun, MySQL’s fate looked uncertain. MariaDB forked to preserve openness, and today powers much of the web. But the ecosystem split—plugins, documentation, and mindshare had to be duplicated.

- LibreOffice vs OpenOffice: After Oracle abandoned OpenOffice.org, the community forked LibreOffice, which now thrives under The Document Foundation. Apache OpenOffice lingers but stagnates.

- OpenSearch, OpenTofu, Valkey: Each fork creates duplication. Communities split, companies hedge bets, and adopters must pick sides.

Forks are proof of resilience, but they also add friction. The very accessibility that once defined open source is diluted.

Why the Cathedral Regained Power

Several forces explain why the cathedral has consumed so much of the bazaar:

- Cloud centralization. Running services at global scale favors massive vendors. Hosting, marketing, and integrating open source requires capital and reach that individuals lack.

- Revenue pressure. Investors demand monetization. Open core, dual licensing, and relicensing are seen as defensive moves to protect revenue streams from hyperscalers.

- Convenience gravity. GitHub, Docker Hub, PyPI, npm—these aren’t just platforms, they are the infrastructure of the bazaar. When corporations own the platforms, they effectively own the bazaar.

- Brand capture. When conferences, docs, and releases carry corporate branding, the perception of community ownership fades, even if the license remains open.

Accessibility Lost

For the next generation of developers, “open source” doesn’t feel as open as it once did.

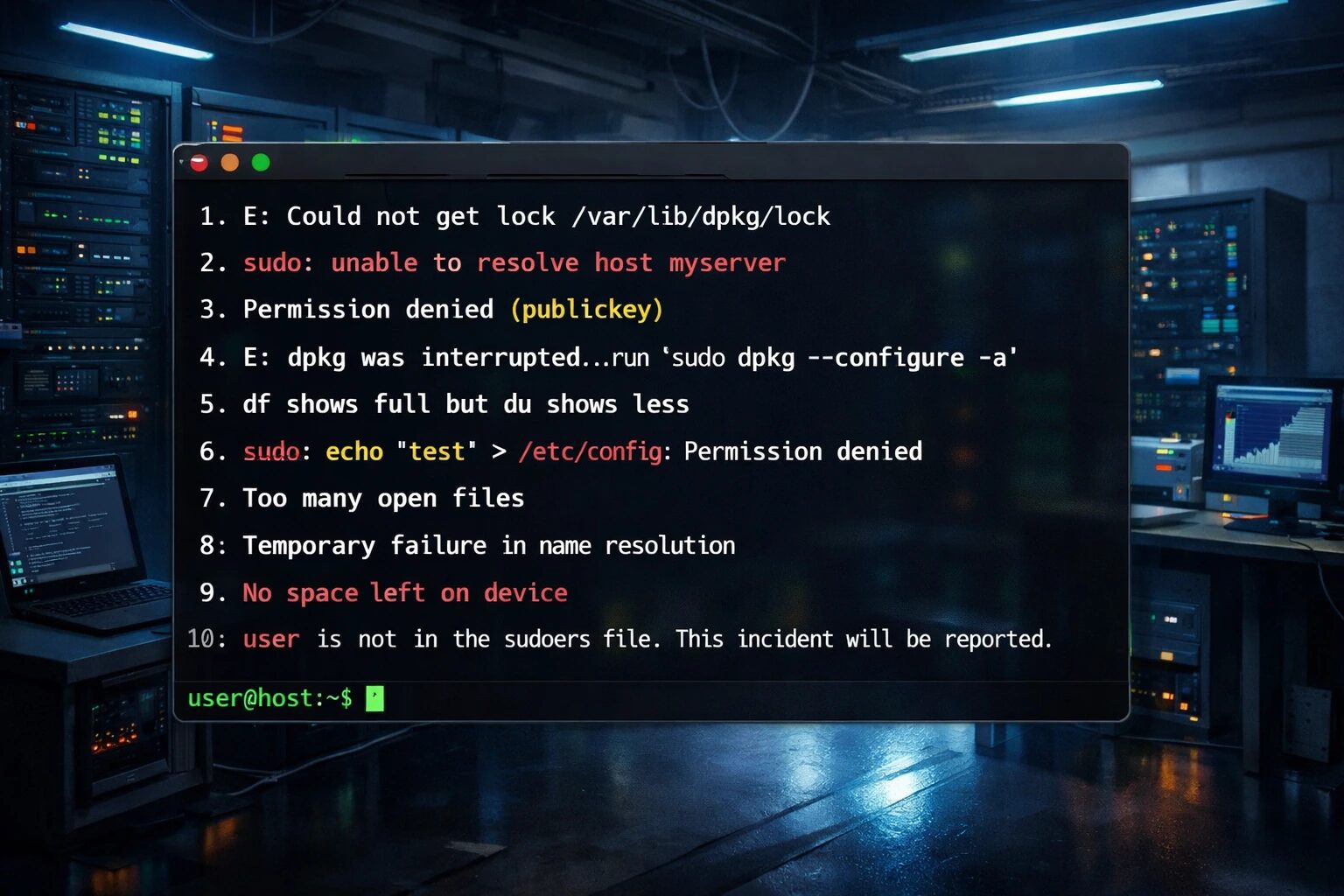

- License anxiety: What used to be copy-paste-and-go now requires legal reviews (Terraform BSL, Elastic SSPL).

- Higher rebuild barriers: RHEL’s source restrictions raised costs for downstream distributions.

- Platform tolls: Docker Desktop’s subscription changes in 2021 introduced gates even when the code remained free.

Accessibility—once the hallmark of the bazaar—has been eroded by cathedral structures.

The Bazaar Still Fights Back

Despite these trends, the bazaar is not dead. Its resilience is shown in:

- Foundation-led projects: CNCF, Apache, and Linux Foundation governance provide neutral homes for projects.

- Forks as immune response: MariaDB, LibreOffice, OpenTofu, and Valkey show that communities can outlast corporate capture.

- New models of sustainability: Crowdfunding, dual-home artifacts, and collective governance experiments are pushing back.

The bazaar still has life. But without structural guardrails, the cathedral will keep buying stalls.

How to Reopen the Bazaar

To preserve accessibility, the open source community needs stronger defenses:

- Adopt OSI-approved licenses. Keep source code truly free; monetize above the stack (support, hosting, training).

- Prioritize foundation-first governance. Place project trademarks, specs, and steering committees under neutral nonprofits.

- Dual-home platforms. Mirror repos, docs, and artifacts across non-corporate infrastructure.

- Transparent relicensing. If licenses must change, require community ballots, migration guides, and sunset periods.

- Procurement reform. Enterprises should preference projects with neutral governance and OSI licenses.

Conclusion: The Future of the Bazaar

Eric Raymond envisioned a world where the bazaar would eclipse the cathedral. He was right—briefly. But the cathedral adapted. It bought booths, restricted licenses, and centralized the platforms.

The bazaar still exists, but it’s fragmented, fenced, and often overshadowed. To ensure that the next generation of developers finds open source as free and accessible as we did, we must fight to reopen the bazaar—with foundations, forks, and governance models that resist capture.

Open source is not just code. It’s freedom, accessibility, and community. If we let the cathedral own the bazaar, we lose more than software—we lose the very culture of collaboration that built the internet.