Why “Windows-Looking Linux” Can Sabotage Your Switch

Switching operating systems isn’t just a technical migration. It’s a habit migration. You’re moving muscle memory, assumptions, and identity—“this is how a computer works”—from one world to another.

That’s why so many people leaving Windows or macOS reach for a Linux distribution that looks like what they’re escaping. A familiar taskbar. A familiar dock. Familiar icons. Familiar menu patterns.

It feels like easing the transition.

But in practice, it can be one of the quiet reasons Linux desktop adoption stalls—or at least why people try Linux, get frustrated, and go back. Because choosing a Linux distro primarily for how closely it resembles your old OS is like dating someone who looks like your ex.

It’s comfort masquerading as progress.

The “Ex Look-Alike” Trap

Visual familiarity signals functional familiarity. Humans are wired this way. If it looks like the same thing, we assume it behaves like the same thing.

So when a Linux desktop mimics Windows or macOS, it sends an implicit promise:

“You’ll be at home here.”

And for the first few hours, you might be. You can find the launcher. You can open settings. You can pin apps. You can drag windows around and think, “This isn’t so different.”

But Linux can imitate the shape of Windows or macOS without replicating the entire ecosystem underneath it.

A Windows-like panel and menu can’t magically bring along:

- the same software distribution model

- the same driver packaging expectations

- the same update philosophy and timing

- the same configuration patterns

- the same vendor integrations and defaults

- the same troubleshooting conventions

So users operate on autopilot. They click expecting old outcomes. They try old fixes. They search old terms.

Then Linux responds like Linux.

And that gap—between what you expected and what you got—is where a lot of “I tried Linux and it wasn’t for me” stories are born.

You Didn’t Leave Because of the Wallpaper

Most people don’t abandon Windows or macOS because the taskbar or dock wasn’t pretty enough.

They leave because of friction:

- forced update timing

- telemetry and privacy concerns

- performance drift and bloat

- hardware restrictions or lock-in

- subscription creep

- a sense of lost control

These aren’t surface-level complaints. They’re ecosystem-level complaints, tied to incentives and design priorities.

So when someone leaves and chooses Linux based on “it looks the same,” they’re often trying to keep the feel of the old relationship while escaping the parts that hurt.

That almost always ends in disappointment.

The False Promise of “Drop-In Replacement”

The closer Linux looks to Windows or macOS, the more it invites a dangerous assumption:

“This will work the same.”

That expectation doesn’t survive contact with reality—not because Linux is “bad,” but because Linux is a different philosophy.

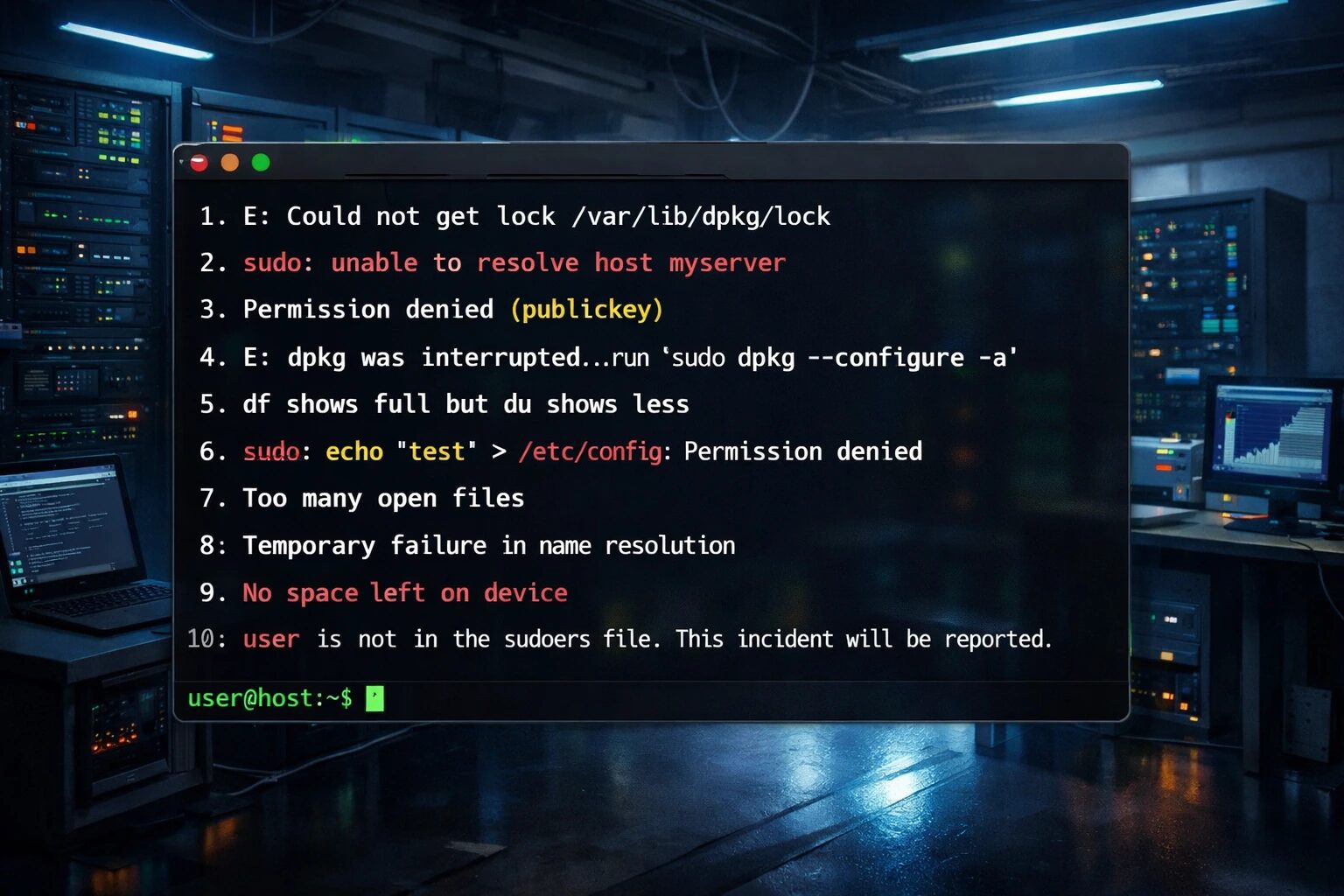

Even common tasks can feel unfamiliar:

- installing applications (repositories vs downloads vs sandboxed apps)

- handling permissions and ownership

- finding logs and troubleshooting issues

- managing updates and system components

- mapping file paths and configuration locations

When the onboarding experience was framed as “basically the same,” those differences don’t feel like normal learning curves. They feel like failure.

And that’s a key adoption problem: users don’t just leave Linux—they leave with a story.

- “Linux is inconsistent.”

- “Linux is janky.”

- “Linux isn’t ready.”

When the more accurate story is often:

- “I expected equivalence where there was never meant to be equivalence.”

Training Wheels Are Fine — Living on Them Isn’t

To be clear: there’s nothing wrong with wanting familiarity in the first week. A comfortable layout can reduce stress and help you stick with it long enough to learn the basics.

The problem is when familiarity becomes the goal.

When your success metric is “Does it feel exactly like Windows/macOS?” you’ve set Linux up to fail—because the more it resembles your old OS, the more you expect it to behave the same.

That’s why the “ex look-alike” approach can hold back broader Linux desktop adoption. It creates a psychological bait-and-switch:

- “Look, it’s basically the same.”

- “Wait, why doesn’t it work the same?”

- “This is harder than I thought.”

- “I’m going back.”

Not because Linux can’t meet their needs—but because the transition was framed around imitation instead of expectation-setting.

A Better Approach: Treat Linux Like a New Relationship

If Linux adoption is going to grow, the story can’t be “Linux is Windows/macOS with a different logo.”

The story has to be:

This is a different ecosystem with different strengths—and it rewards a different mindset.

The best Linux transitions happen when people choose the OS for the right reasons:

- stability

- control

- transparency

- community

- performance

- flexibility

…and they expect differences. They stop trying to recreate their old workflow pixel-for-pixel and instead learn the Linux workflow on its own terms.

That mindset shift is the real breakthrough:

- Instead of: “Where is the Windows way to do this?”

- You move to: “What’s the Linux way?”

When that happens, differences stop feeling like betrayals and start feeling like features.

Don’t Date Your Ex

If you’re leaving Windows or macOS for a reason, honor that reason. Don’t rebuild the same environment and then get upset when it isn’t identical.

Linux isn’t trying to be your old operating system. It’s offering a different relationship with your computer—one built around choice, ownership, and control.

And the “it looks like your ex” strategy may be one of the most underrated reasons people try Linux, get disillusioned, and retreat back to what they already know.

The way forward isn’t perfect imitation.

It’s better expectation setting.

Don’t date the look-alike.

Meet Linux as itself.

Learn the workflow.

And you’ll be far less likely to “try it for a weekend” and go back Monday morning.